A VR project makes visitors explore the musicality of their everyday existence. Author Steffen Greiner took a deep dive. A report from the “Symphony of Noise”.

On the S-Bahn to the Reeperbahn: the guy beside me is nervous. That makes me nervous in turn, the way he taps the window with his index finger. You barely hear it, but the rhythm is fast and insistent. I try to look away. What I don’t try to do is dance. What would my world be like, at this moment, if I closed my eyes, thought of the window as an instrument, a resonating body, and the nervous guy beside me as a composer, adding his miniature works to the city’s sound?

Our bodies as instruments

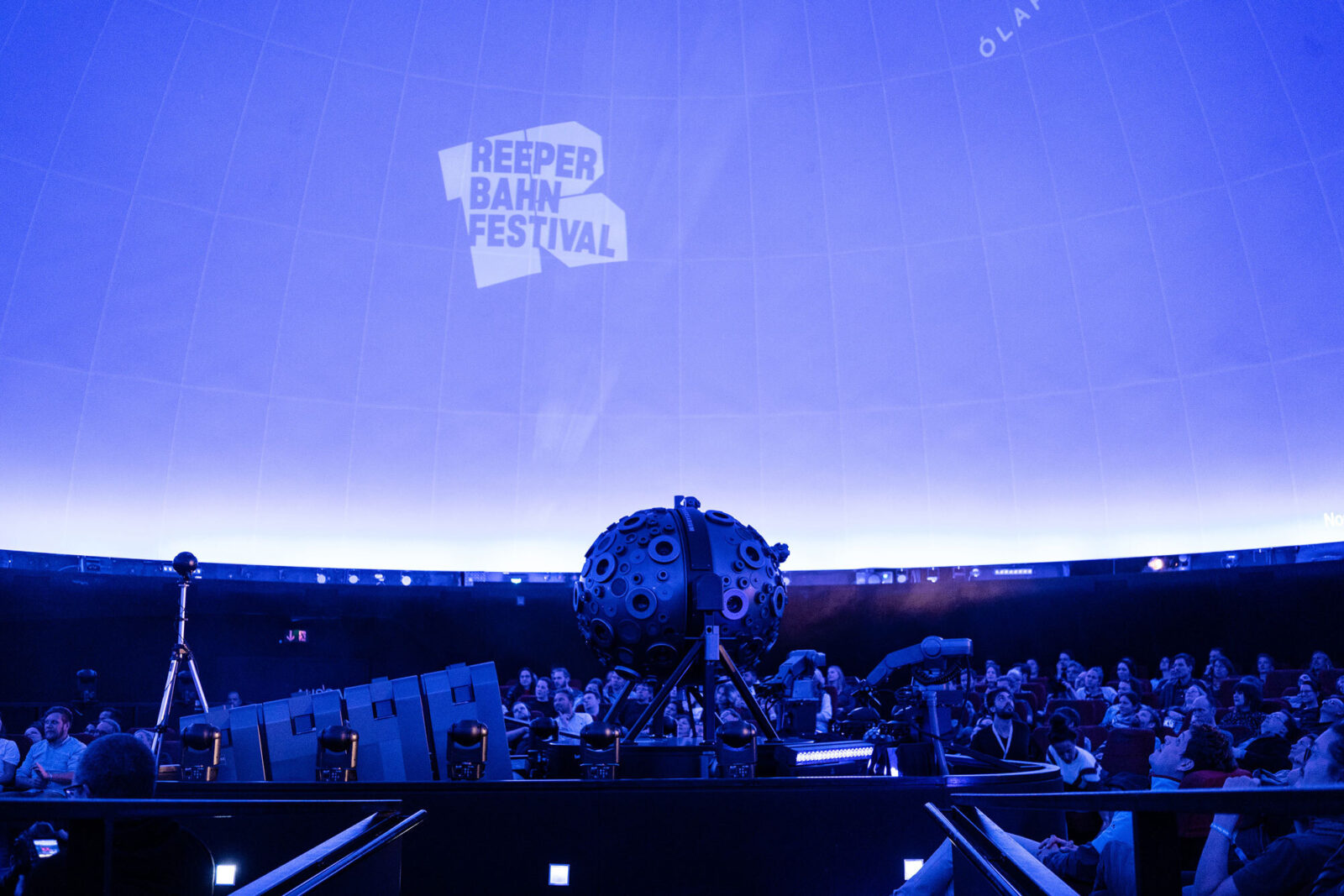

“A Symphony of Noise” is the very promising title of a new virtual reality experience that is premiering on the Heiligengeistfeld in Hamburg. A year and a half after the first prototype, the project has moved into a deep-sea container at the entrance to the Reeperbahn Festival’s Arts Playground. There, the makers on creative director Michaela Pňačeková’s team have set up their generator of virtual worlds that feed on everyday sounds and the users’ input. The starting point for the VR trip is a book by the British house producer Matthew Herbert, displayed unobtrusively in the antechamber of the container, which is divided by a black curtain: “The Music” is a novel through sounds. In virtual reality, it now finds an artistic extension.

Herbert, whose first albums were released back in the mid 1990s, always did more than just churn out dance music. For the "One Pig" album, for instance, he took recording equipment and shadowed a pig from birth till its death in the abattoir. You could call it Musique Concrète, avant-garde music from existing, renegotiated sounds. But even more than this 1960s genre, Herbert is about politics and responsibilities.

Divorced from what we generally call 'music', what does the system sound like – in other words with all the high-fives and that cough and the fingers hitting the keyboard? In his book, a series of scenes describes poetically the creaking of tectonic plates and the hum of refrigerators – and in between, life, our bodies as instruments.

Disinfection before poetry

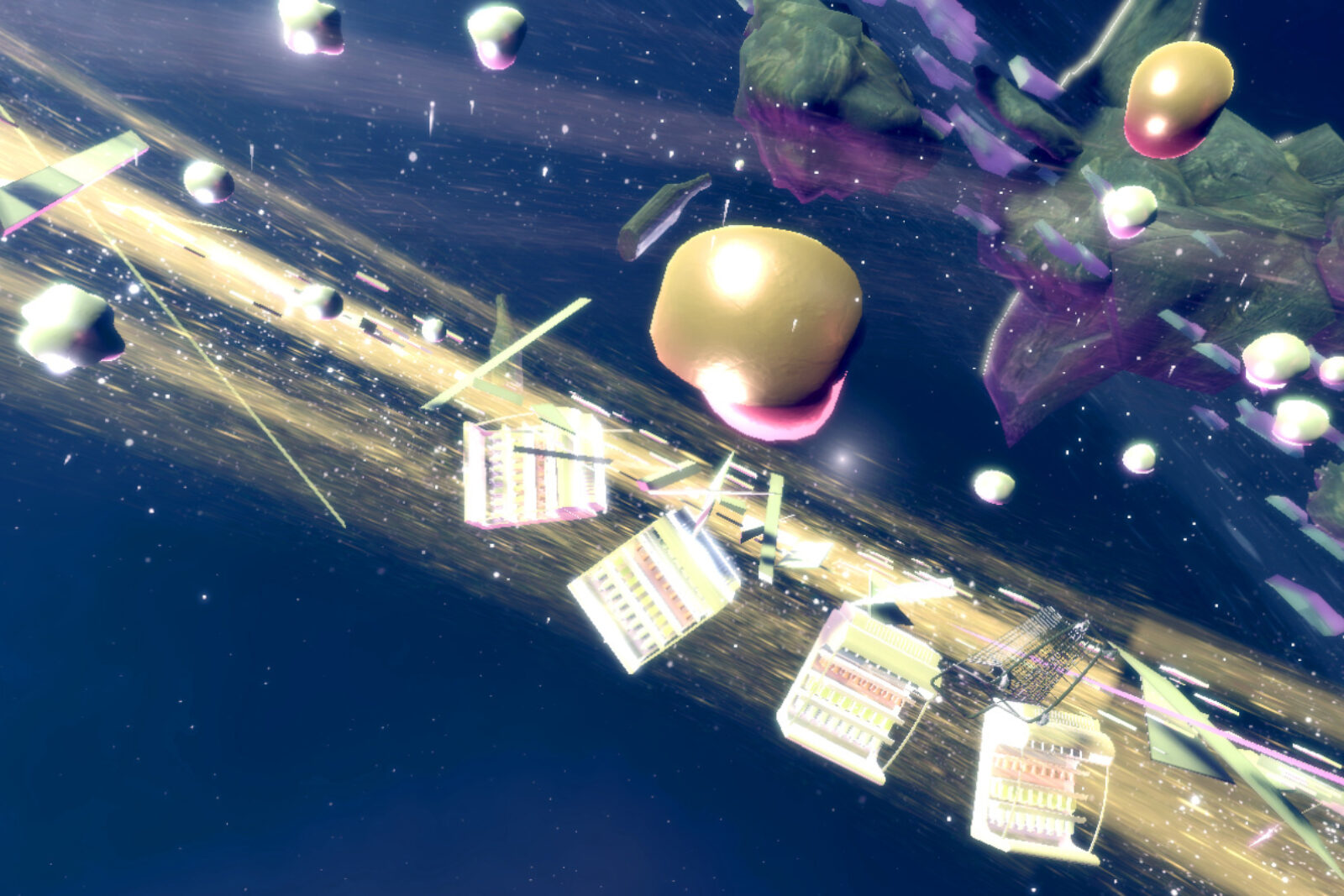

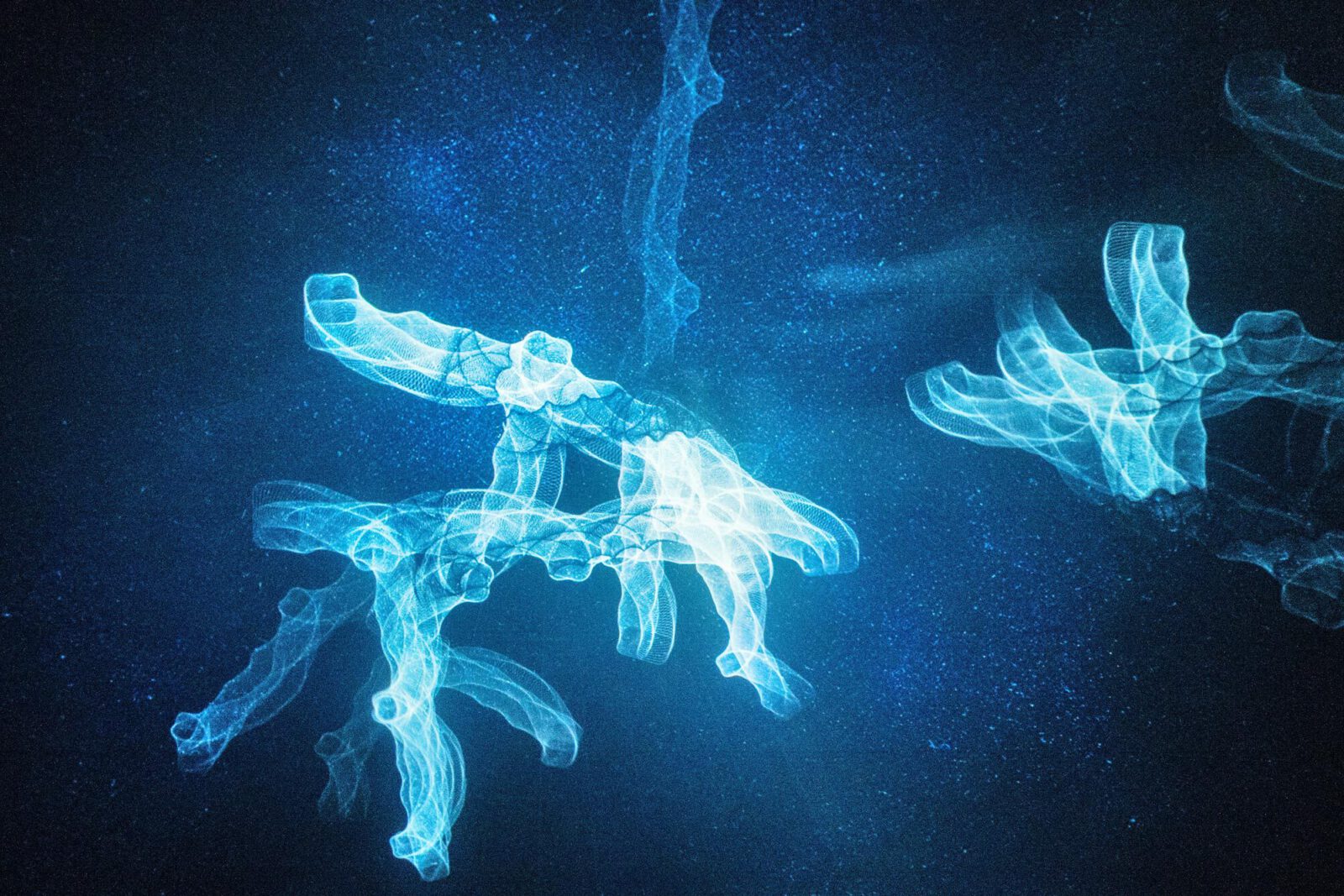

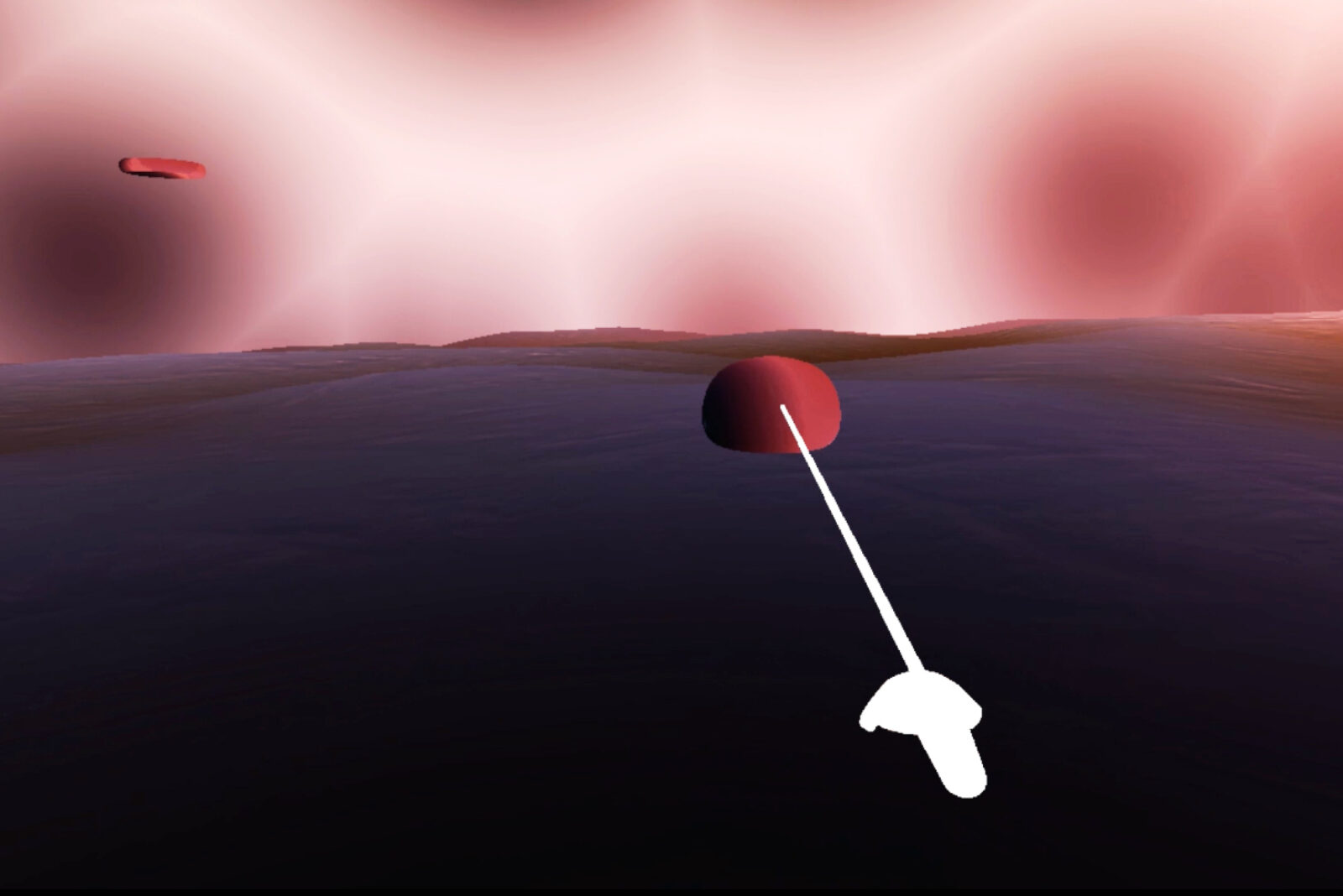

Where Herbert finds language for sounds, the project finds sounds and visualisations for his worlds. Producer Michaela Pňačeková says that the “Experience” is intended to describe a journey from the interior to the exterior. “To start with we wanted to create very concrete worlds. But we realised that the sounds people create are already so concrete that everything had to be aestheticised. I wanted it to be surreal and Sci-Fi, I wanted David Lynch”. To bring the miracle of the sound of voices, bodies and simple rhythms tangible, the environments are intended to give them a stage, not upstage them. The very real sound of my body in visual, virtual poetry.

Before the poetry comes disinfection, at the back of the container, behind the curtain. The device I’ll be wearing in a minute is more than goggles, it’s an entire complex, and we wearers are sweating profusely over it on this summer day. Lilian will be my companion as I enter the worlds that await me. While she prepares my goggles, headphones and microphone, she explains what lies in front of me: she talks of singing, breathing, of objects that I can activate with two controls. We tweak the equipment thoroughly till my head finds itself wrapped in total isolation, all viewing slits are closed and the image focused. Then I turn round and take a deep breath. The new worlds weigh heavy.

The fact is: I’m singing. And I’m enjoying it.

All around me is a red desert. Text and spoken words explain what I’m supposed to do. My breath can influence reality here. I breath in and slowly out, through the mouth, through the nose, and nothing happens. So what’s supposed to happen here? I discover a billowing object. When I blow on it, it gets bigger. And the harder I blow, the more the mass above the red infinity balloons up. That interests me. I take a deep breath, blow into the microphone as hard as I can, till the sky is filled entirely with a transparent, glittering, soap-bubble-slimy object. Then everything goes white.

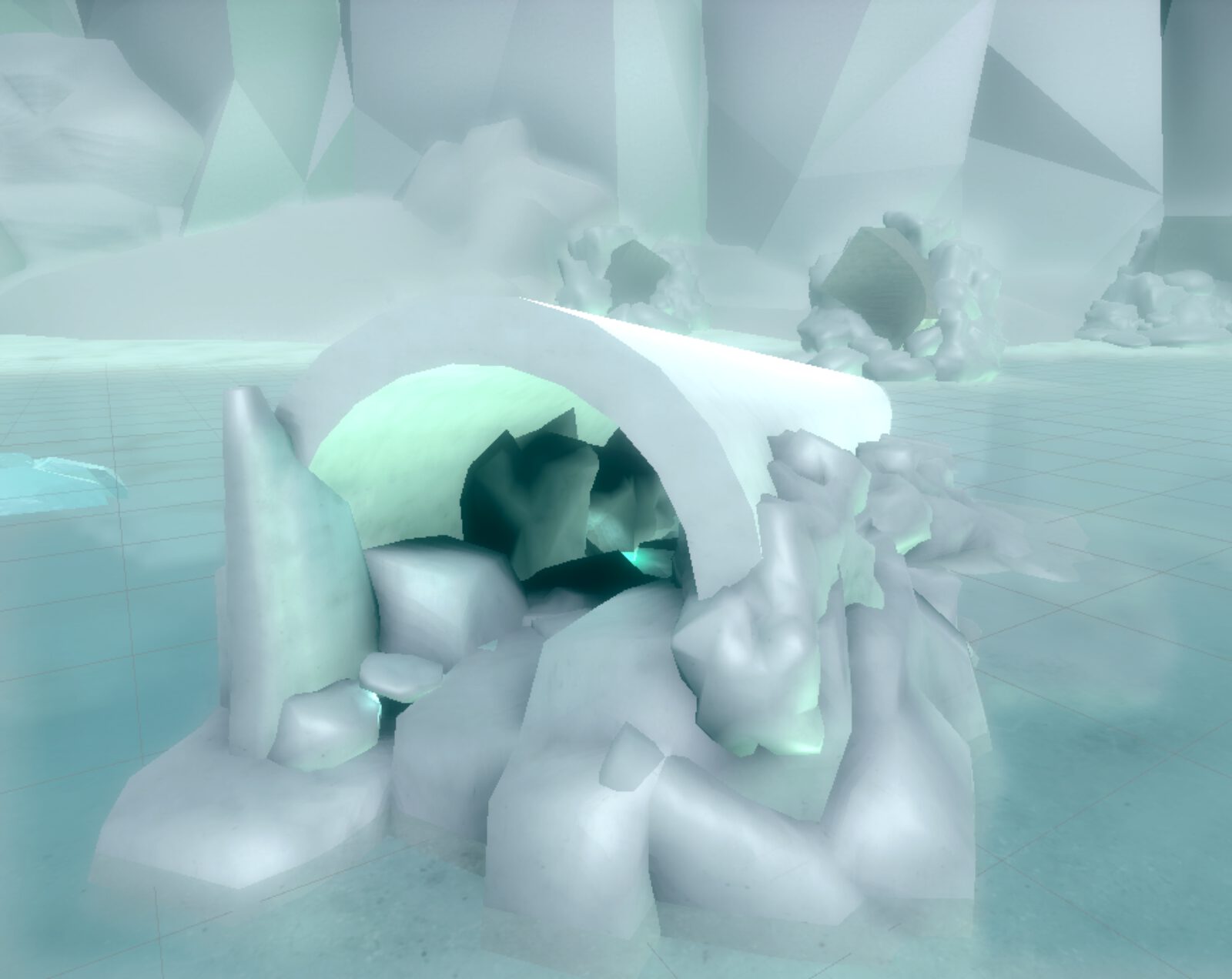

When I’m told to sing something into the landscape of rugged icebergs that towers up in front of me, the only thing that comes to mind sounds like a mixture of half-remembered early Sigur Rós and that triumphal-baroque fanfare I once sung into my mobile phone on an excellent trip in a forest in the Harz mountains. Happy-making associations, sure, but my heavens: why sing these Iceland sounds in such an Iceland environment, and why not Tamikrest or Olympia? The fact is: I’m singing. And I’m revelling in it. And the world responds, as the tunnel that’s carving itself into the ice in front of me throws back my sound and expands further as I get louder. I won’t remember that Lilian and our photographer Tom are standing just a metre or so away until she removes my equipment some ten minutes later.

As I stand sweat-drenched in front of the container, back on the Heiligengeistfeld, I’m not quite with it. No, I’m not hearing the world with different ears, but the happiness I felt in these solitary, poetic worlds, which I was capable of filling entirely, with my voice and my body, is still reverberating in me. At night in the empty S-Bahn to Berliner Tor, I notice how wonderful the window panes sound when you flick at them with your fingers. Like a lunatic, or like a composer.